“I believe that life is a continuum, and that no one really dies, they just drop their physical body and we’ll all meet again, like the song says. It’s sad but it’s not devastating if you think like that… We’re all going to be fine at the end of the story.” - David Lynch

It is death, precisely, which makes us alive. Without the promise of mortality we wouldn’t be human. The end of life is inevitable. So, if you love life, shouldn’t you love death? Shouldn’t we welcome it? Yet we don’t— our only experience is the life we currently live, and we have neither a trial run nor rerun, so when someone departs from the only life experience we can conceive, even if we work to love and embrace it, we can’t help but lament it.

It’s hard not to think about David Lynch’s death, not only because he’s the greatest American auteur of all time— now simply dust in the wind— but a man whose work, if you view it through a mortal lens, primarily concerns death. From his debut, Eraserhead, about a mutant baby in a post-apocalyptic nightmarescape of vague industry, to the legendary Twin Peaks TV show about unspeakable malevolence in a small town, to his last film, Inland Empire, about a Hollywood actress’ fracturing sanity, his work is imbued with a sincerity about good and evil that’s unmatched by his contemporaries or anyone who came before him.

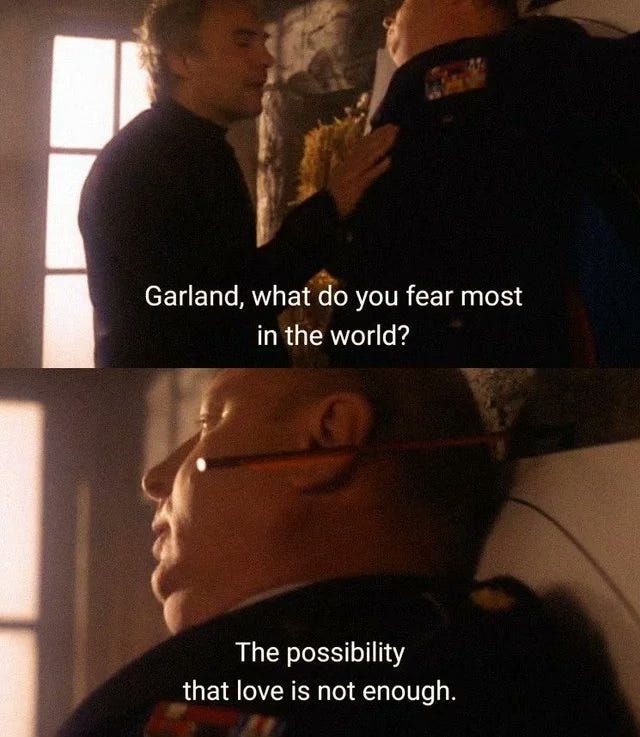

The main question of Lynch’s work, evidenced by my favorite scene from Twin Peaks, is this: in a world so harrowingly evil, is the love and goodness of an individual enough? Does it even matter? By all accounts, David Lynch was a good guy. He saw the virtue in people and enjoyed the little things. But it’s clear from his films that beneath the good old American boy archetype he presented (instilled in him from his Missoula, Montana upbringing), he was acquainted all too well with the evils that men do. He often said the surrealist nature of his work came from dreams he had, but he really meant nightmares— and nightmares are embodiments of terror we know. For all the Redditors and tin-foil hat conspiracy theorists that have spent the better part of the last 50 years trying to “crack the code” of Lynch’s obscured characters and loose narratives, his work is far more accessible than he gets credit for. It’s about the vanity of goodness, systemic misogyny, and the evils that pervade every corner of respectable society. Viewed from such a perspective, Lynch’s work ties together and makes complete sense.

From a wider scope, his work boils down to this (which is why I think it will help me, personally, as a huge fan, cope with his departure): life is scary, but it’s beautiful. For all the evil and chaos in this world, the only thing that matters is to be good to yourself, even if nobody hears you. Further, death isn’t scary; time is a flat circle, everything is a cycle, and death is the only part of life that all of us share in equal measure, aside from birth. In the sense of shared human experience, which gets to the heart of every great artist’s work, death isn’t that scary. Knowing this, it’s easy to see Lynch has been dropping hints about mortality and its edifying nature for his entire career: the nameless singer in Eraserhead repeating to us that “in heaven, everything is fine”, or the freshly dead Laura Palmer hearing the voice of love for the first time in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me.

A filmmaker whose work is so innately tied with dread and inevitable death, the only time Lynch’s characters feel a sense of comfort, happiness, and self-actualization come when death has reared its head. Nobody likes death, especially those who like life. But why is it, then, that some of the most content and tranquil among us are accepting of death, and even welcoming? I saw my grandfather, whose fear of his own mortality became a running joke in my family, instantly accept his fate once he was diagnosed with stage four lung cancer; a wave of serenity washed over him, and he spent his last six months happier than his first 84 years. This happens to many people once the surety of death transcends the abstract and becomes immediate. David Lynch was just blessed to understand this at an early age, before he looked death in the eyes.

So, rest in peace to a guiding light through all the world’s evils. Like the Log Lady said, “it’s just a change, not an end.” And now he’ll finally get to experience the other side. See you on the next cycle, David. Safe travels, and don’t worry about us— we’re all going to be fine at the end of the story.